Cuaming Island, Philippines

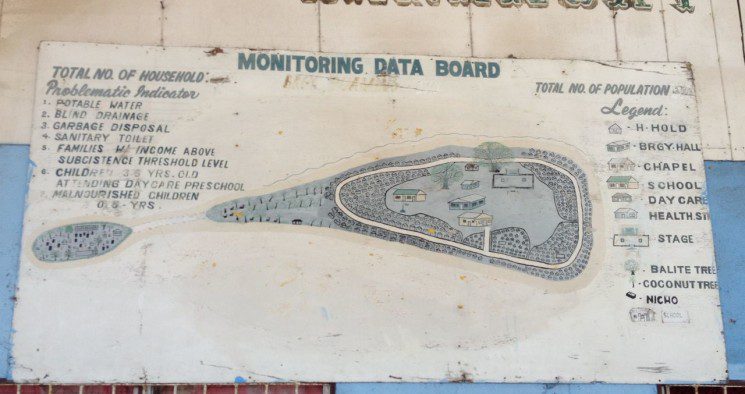

Rogelio Angco traces the neat rows of numbers with his finger as he recounts the details of the ‘Barangay Profile’; the chart framed above his desk. This table keeps a meticulous record of the makeup of the community inhabiting the tiny island of Cuaming in the central Philippines. Each detail has its own row along the wall: how many children in school; how many senior citizens; how many unemployed. The columns mark the years, plotting changes in the community’s population year on year.

The tropical waters around Cuaming are a lifeline for this island community, Angco explains, over 90% of which depend on fishing for food and income. Sandwiched between the islands of Bohol and Cebu in the central Visayas, Cuaming is little more than a sandbank on the outer rim of the Danajon Bank, one of the world’s only double barrier coral reefs. Surrounded by some of the planet’s most important ocean ecosystems, Cuaming lies in the ‘coral triangle’; the global epicentre of marine biodiversity.

Yet life here is a far cry from paradise, and as Barangay captain of this island Angco (or ‘Cap’ as he is known locally) is only too aware of the challenges facing the future of the 3,129 people listed on this year’s ‘population’ line on the wall. He knows that Danajon Bank’s fragile reefs and fish stocks are being pushed to breaking point by the pressures of the region’s burgeoning population.

“Every year the fish we catch are smaller and fewer”, says Angco, as we take a walk on the hot sand around the island’s perimeter. “It’s harder than ever for us to make a living from fishing.” Recent surveys showed that less than one percent of the 90-mile long Danajon Bank’s reefs remain in good ecological condition – the vast majority now decimated from years of overfishing.

Waves of floating plastic lap the shore as we walk and talk. With no system for organised disposal of solid waste or garbage the island is surrounded by a sea of floating rubbish every high tide, much of it carried across the water from Cuaming’s larger neighbours and left on the beach here. Glinting on the horizon in the late morning sun we can just make out the skyscrapers of Cebu, home to over 2 million people and the country’s second city, just 29km west of Cuaming.

The Philippines has one of southeast Asia’s poorest and fastest growing populations, expected to pass 100 million within 14 years. Census data show that population growth in remote coastal villages like Cuaming – where education is poor and access to reproductive health services is very low – is generally much higher than elsewhere in the country.

Decades of neglect of women’s reproductive rights have taken their toll. According to the United Nations Population Fund, half of pregnancies across the Philippines are unintended; one in three are aborted, often by non-professionals in dangerous and unsanitary conditions.

Three months ago, a long-awaited reproductive health bill became law, integrating responsible parenthood and family planning efforts into the government’s development and anti-poverty agenda. It had been blocked for years by out-spoken opposition from the Roman Catholic Church and conservative groups.

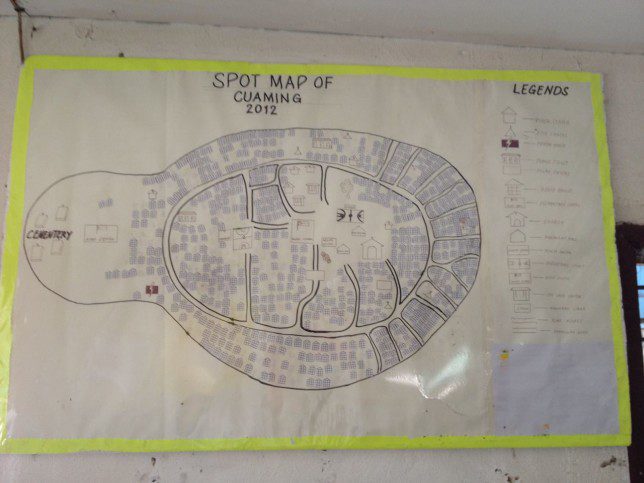

A painted map above the door to Angco’s office plots the homes of each of Cuaming’s 579 families. Viewed from above this island is a continuous wave of shimmering silver roofs crossing the island from beach to beach. Some homes are built on stilts above the water – a brave investment given the island’s vulnerability to violent typhoons. Only a thin sliver of sand at the southern end of the village – the community cemetery – is free from construction.

With no fresh water, only sporadic electricity from a geriatric diesel generator, and no facilities for storing or processing their catches, Cuaming’s fishers depend on buyers from Cebu visiting the island. These fish collectors provide essential access to markets, but also set the price paid for the day’s catch – around 80-120 pesos (2-3 dollars) per kilogram of fish.

Faced with ever diminishing landings, some fishermen resort to using dynamite, cyanide and scuba-assisted fishing to augment their catches. All illegal, these techniques have been widespread in the Philippines since the 1980s, with devastating consequences to the underlying reef ecosystem. Cuaming’s close-knit community has made promising headway in reducing these practices, but even here we pass a boat boasting a large air cylinder and reels of luminous green diving hose mounted across its wooden outriggers, moored in plain view of the village.

Angco remains determined in the face of the threats to his island’s way of life. “We can’t just sit back and watch things get worse,” he explains. Like many coastal villages in the Philippines, Cuaming is taking active steps to tackle the pressures of overfishing head on. Seventy-four hectares of coral reef and seagrass meadow around the island have been set aside as a sanctuary, within which fish stocks can replenish, and – it is hoped – overspill to help replenish fished areas. A nursery of mangrove seedlings now fringes the edge of the lagoon, and one in ten families now supplement traditional fishing income by cultivating seaweed on buoyed lines in the shallows around Cuaming.

Yet despite broad community support, Cuaming’s precious sanctuary remains vulnerable to the rampant illegal fishing elsewhere on the Danajon Bank. Enforcing the rules comes at a cost. The reserve’s marker buoys are expensive, and need to be replaced regularly – not easy when working with an annual budget of just 5000 pesos per year (around $12) from the local municipality. To compensate, the village takes it upon itself to help protect its marine investment. Strengthening local respect and support for the sanctuary is vital.

Marine biologist Jeremy Jansalin works on Cuaming with the PATH Foundation, a Filipino NGO supporting local communities in dealing with the environmental and social challenges they face. “Here in Cuaming, fishermen take turns on rotation day and night to keep a watch for poachers in the reserve,” he says. “Everybody here understands that without constant surveillance, everything that they have worked so hard to preserve could be destroyed in a matter of hours.”

“The sanctuary is a big help – it’s like a marine bank, a nesting place for our fisheries, helping us produce more fish,” says Angco. During my visit he and Jansalin study a blueprint for an ambitious floating bamboo guardhouse, on which designated community watchmen will spend the night, moored in the middle of the sanctuary.

Marine sanctuaries are a widely adopted approach throughout much of the Philippines, with the Danajon bank boasting 83 marine protected areas similar in size to Cuaming’s, and at least 170 around the adjacent island of Bohol.

However this community’s efforts go much further than conserving coral reefs. When they are not busy discussing the merits of using night vision binoculars to catch poachers, Jansalin and his colleagues work with women’s groups, schools and youth clubs, providing training and support through activities ranging from seaweed farming and processing to voluntary family planning.

The family planning projects have been widely welcomed on the island. Reproductive health specialists train networks of adult and youth ‘peer educators’; volunteers who work throughout the community to ensure all women have access to contraceptives. These specialists also help both men and women understand the connections between family size, food security and household income.

“Often men are driven to poach in sanctuaries just to feed the family,” explains Ramon Menguito, President of Cuaming’s People’s Organisation, which represents the island’s fishermen. “But they know that it is becoming harder and harder to find enough fish to live on – both for their families to eat and for them to sell.”

Jansalin’s shirt carries a cartoon depicting a circle of hands grasping for single fish. An appropriate message on an island where a shortage of fish means families regularly go hungry. “This integrated approach to conservation is working not only to help fish stocks recover, but also to tackle one of the underlying causes of declining fish catches,” he explains. “For it to work, the support of the community here is absolutely vital.”

Since the PATH Foundation’s work began here, population growth has stabilised. Almost everyone I meet is keen to tell me why the project works for them. “Our sanctuary won’t survive without family planning,” says Anita Manalo, President of the Women’s Association. “And if the sanctuary doesn’t survive, then life will become harder and harder for us because we are running out of fish.”

Cuaming’s pragmatic approach to integrating environmental protection alongside economic development and family planning represents marks a change in the conventional thinking that guides many marine conservation initiatives today. This village is just one of many thousands of coastal communities in this region in which the issues of conservation, food security and reproductive health are intimately interlinked. Yet Cuaming’s partnership with the PATH Foundation remains one of few initiatives working in a truly integrated way to address the convergence of these complex issues.

Before we leave the island we pass by the community health clinic, where Susanna Lopez, Cuaming’s community midwife, greets us. She has just delivered the island’s newest resident, a baby girl less than one hour old. Angco smiles as he remarks that the chart on his office wall will now need an update.

Our small boat weaves through the submarine forest of seaweed farms – a necessary detour to avoid fouling the propeller on the network of seaweed lines hanging just beneath the surface.

As we motor back to Bohol I wonder what the future holds for Cuaming’s 3180th resident. The UN’s 2013 Human Development Report predicted this month that up to 3 billion people could be living in extreme poverty by 2050 unless urgent action is taken to tackle environmental challenges. Danajon Bank’s coral reefs are living on borrowed time, yet the PATH Foundation’s inspiring work with local leaders like Angco has proved that communities can lead effective initiatives to help more forge more sustainable futures.

///

Alasdair Harris visited Cuaming in March 2013 as part of ongoing efforts to share experiences of integrated Population-Health-Environment (PHE) programming between Blue Ventures and the PATH Foundation.

A shortened version of this article originally appeared on the Guardian Global Development Professionals Network.